Reimagining India’s Role In South Asia – The China Factor

By Rajesh Mehta and Govind Gupta

February 15, 2021

There is an ongoing churn in South Asia and the pandemic provides a propitious window for South Asian countries to abandon traditional concerns and take collaborative action.

To tweak a running joke “the war between US and China is over and the winner is Asia”

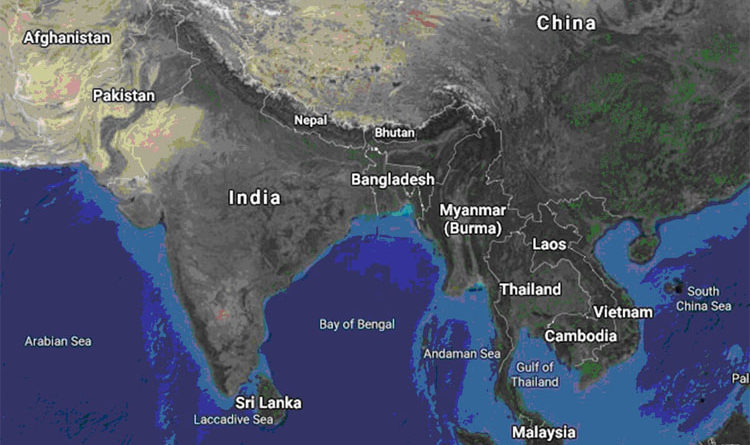

Actually, even with the Biden administration, as evinced by the recent tensions in the South China Sea, the tussle is far from over, yet the punchline reveals a crucial development: With the US retreating from global commitments and China’s state-driven model sprawling its sway, the time is exigent for a new narrative, provided by the promise of Asia ex china, to level the world order. For far too long, the economies of this region have been hedging their positions, trying to manoeuvre the two superpowers, but a trust deficit and scepticism about China’s debt-trap diplomacy along with a fickle US turning inwards, necessitate that the region creates a strategically significant economic position of its own. The crucial component for this will be the integration of South Asia.

There is an ongoing churn in South Asia and the pandemic provides a propitious window for South Asian countries to abandon traditional concerns and take collaborative action. The crucible of crisis holds promise for unprecedented actions: the European Union and ASEAN stand testament to such regional engagement, serving as a template for South Asia.

Despite a shared cultural history, there exists sparse cross-subregional economic integration through trade or investment in South Asia. Its integration with itself as well as with the South East remains dismal. South Asia’s intra-regional trade is the lowest globally, constituting only 5% of the region’s total trade. The current integration is just one-third of its potential with an annual estimated gap of $23 billion.

Moreover, emerging scarred from the pandemic, with many South Asian countries taking a relatively severe economic hit, the region needs to position itself for recovery on a sustainable and accelerated growth trajectory. With policy tools exhausted, vital growth tailwinds can be realized from integrated markets and trade liberalization.

With the stars aligned both demographically, and economically, integration is opportune for the region to strengthen itself to attain the shared goals of inclusive development. But as per the ‘bicycle theory’ where standing still isn’t an option and one needs to keep moving, proactive efforts to lower barriers to trade and investment would be indispensable to attain the integration.

With the youngest population in Asia (a median age under 27) along with the fastest growth rates, the region could account for about one-third of global growth by 2040, as per World Bank. But the critical enabler would be ambitious liberalization in trade and FDI. The promise lies in the extent of untapped potential which can be realized through increased connectivity and cooperation.

South Asia’s trade integration is lower than the global average, and it is way less integrated into global value chains compared to East Asia. Due to the absence of serious economic coordination, average trade costs within the region are 20% higher than the corresponding costs within ASEAN. The countries have abysmally low exports due to the low productivity of many countries in this region. They can catch up in productivity only when competitive pressures and assistance through knowledge spillovers are unleashed through intra-regional trade.

Transaction costs in trade when reduced through Free Trade Agreements and removal of Non Tariff barriers like red tape, clunky licensing requirements or cumbersome sanitary or phytosanitary rules on food, could accelerate nations to reach their trade and growth potential. Besides, due to increased digitalisation post covid, firms will be better able to coordinate supply chains and logistics over the region. Concerted efforts to coordinate as one South Asia economic bloc, establishing regional value chains, capitalizing on trade linkages and productivity gains from technology transfers, are imperative to attain this promise.

Economic integration and cooperation expand the market for goods and services, facilitating economies of scale and efficiency. Moreover, the diverse set of comparative advantages in this region will enhance capabilities and overall regional competitiveness. The next wave of trade for this region will be driven by an increased share of services. Countries in South Asia have demonstrated a tendency to leapfrog towards digital technology, placing them favourably to ride on the rising tide.

Corporates from the west have been vying certain emerging Asian markets to invest in and create a bulwark against China’s ambitious expansions in the region. Besides, in a low-interest-rate environment along with secularly stagnated advanced economies, capital is seeking opportunities which promise higher returns. Firms are looking to re-shore manufacturing closer to final consumers and would prize the highly populous and growing countries like India and Bangladesh. A more integrated South Asia would attract higher FDI due to this enlarged market access and a facilitating milieu of regional value chains. Furthermore, increased financial integration will also enable Asia’s own high savings rate to be put to use more efficiently through investment in the region.

Unification of the region will not only yield economic gains but also serve to address development concerns by helping nations close poverty gaps and attain food and energy security. The World Bank estimates that regional cooperation and engagement will yield energy savings of about $17 billion in capital cost reductions through 2045.

The economic bloc would need cooperative investment strategies to ensure cross border infrastructural connectivity and flows. Improving the physical transport infrastructure is pressing for creating an economic corridor as the current state of logistics is stifling trade and offsetting the upsides of proximate geographical positioning of these nations. Lower container-port performance makes shipping cost double and take 50% longer in South Asia than what it does in the South East. Improving port efficiency requires collective efforts by countries, making cross border infrastructural investment even more pressing.

India will be an integral facilitator and component to this economic bloc. At a time when other countries are gripped by vaccine nationalism, India’s unparalleled leadership in vaccine diplomacy by reaching out and assisting other countries places it favourably to further the interests of this integration. Moreover, it needs to quickly initiate the efforts by leveraging its goodwill in the region else China will be swooping down. Being the largest economy here, it can lead the process by advancing trade policies and cross border solutions to shared roadblocks.

Lately, China’s investment loans through the Belt Road Initiative have come under a cloud. They come with strings attached and don’t allow the local population to be employed in the construction works. There are simmering sovereignty concerns as sceptics view this as a strategy for advancing Sinocentrism in Asia.

With South Asia poised for a growth takeoff and emerging as a dynamic and significant bloc, it can become a reckoning force in the geopolitical order and even the playing field which Beijing and Washington try to dominate.

Existing associations (like SAARC) haven’t been able to significantly advance regional cooperation here. By taking an economic stake in each other, countries stand to realize sustainable shared prosperity, while also ensuring cross border truce. Delinking domestic sentiments from the economic rationale, engaging in diplomacy to allay concerns should be the way forward for countries which do have qualms about the integration.

Albeit, the challenges due to diversity, disagreements and security threats make this a daunting task but lots of potential big bills can be picked up if countries engage in serious efforts to advance the cause. The economic case for integration is compelling, the question is whether political will can prioritize economic prosperity or not.

(Rajesh Mehta is a Leading International Consultant and Columnist working on Market Entry, Innovation & Public Policy. Govind Gupta is the co-founder of IFSA Hansraj and researcher at Infinite Sum Modeling, Washington. Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of the Financial Express Online.)

Courtesy: FE Online